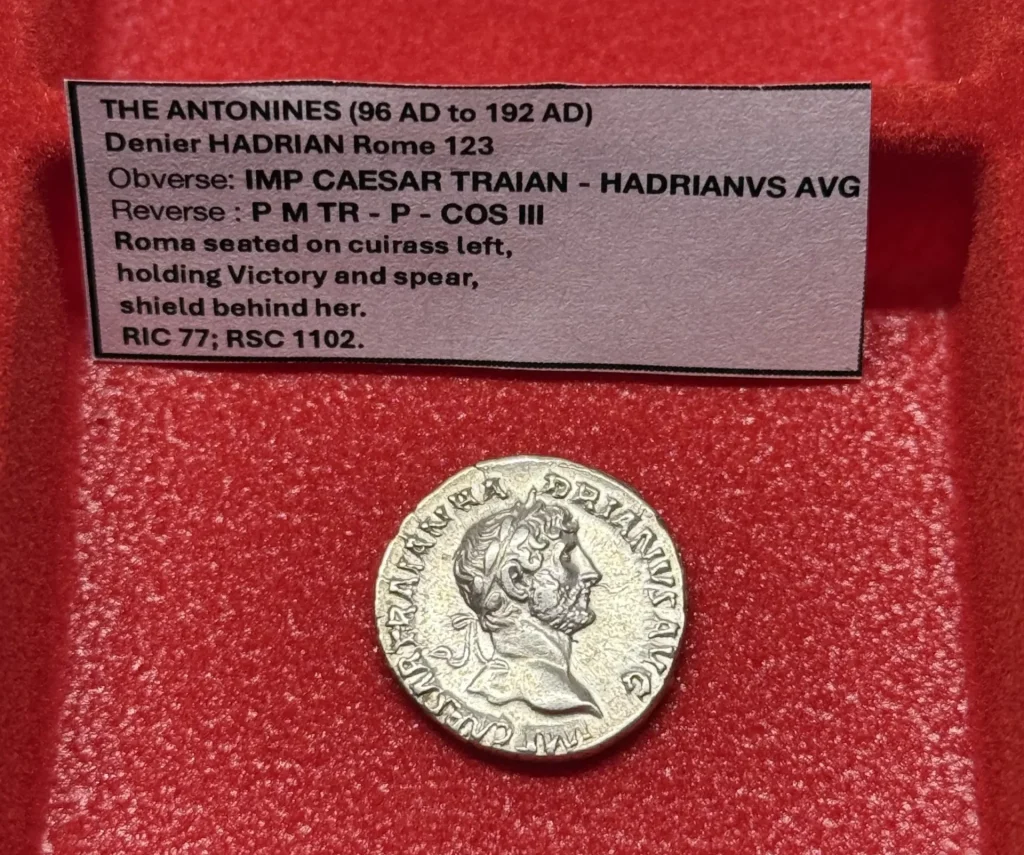

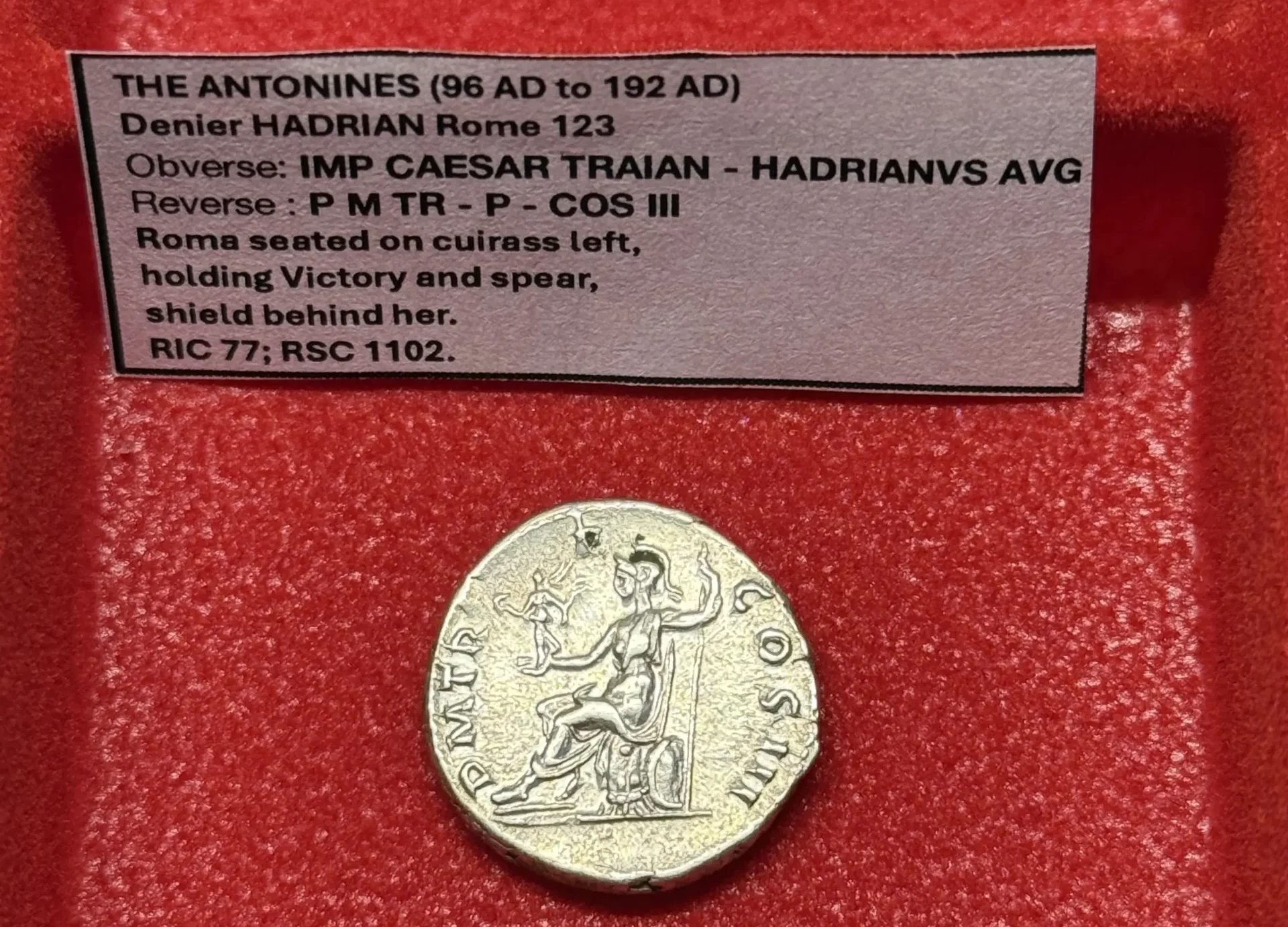

I recently acquired two Roman silver denarii struck during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. Adding these coins to my collection became the impetus to research one of Ancient Rome’s “Five Good Emperors.”

Hadrian was not an emperor who ruled from behind palace walls. He was a restless wanderer, a ruler who believed that to truly govern an empire, one must see it, touch it, and understand its people. Ancient Rome had the unique ability to absorb its territories- not simply conquer them. Unlike many of his predecessors, Hadrian did not spend his reign in Rome; instead, he traveled across his vast empire, leaving behind fortifications, cultural revival, and a legacy of stability that would shape the Roman world long after his death. Today, we remember Hadrian for a truly humble Emperor. He faced his fair share of struggles, especially as Parthia once again tested the waters with Rome’s legions.

A Childhood Foretold

Hadrian’s early years were marked by two cataclysmic events: the grand opening of the Colosseum and the eruption of Mount Vesuvius that buried Pompeii.1

The Emperor Who Saw Everything

Dio Cassius, the historian, wrote that Hadrian personally viewed and investigated absolutely everything.1 This was not an exaggeration. From Britain to Egypt, he traversed his empire, inspecting forts, reviewing soldiers, and speaking directly with local leaders. A grand party followed him through most of Britain as the Emperor went about his tour. Unlike many rulers who governed from a distance, Hadrian got his hands dirty, ensuring that he truly understood the lands under his rule. His most famous project, Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, remains a testament to his strategic mind and hands-on approach to empire management. It is one of the most popular tourist locations in Northern Britain.

Legions and Legacy

One of Hadrian’s greatest contributions was his reorganization of the Roman legions. He focused on strengthening defensive positions rather than aggressive expansion, understanding that Rome’s future depended on maintaining stability rather than endless conquest. I think that this is Hadrian’s most notable trait, or at least how history remembers him; for he was interested in quality over quantity when it came to provincial rule. What I mean by this is that Hadrian saw the value, or rather lack of, in ruling over territories that offered little return on investment.

A Practical Approach to Christianity

Unlike many emperors, Hadrian did not persecute Christians purely for their beliefs. Instead, he insisted that they only be punished if they were guilty of actual crimes. This was a nuanced approach for the time, showing that he viewed governance as a practical matter rather than a tool for ideological persecution. While he was no champion of Christianity, his policies likely helped prevent harsher crackdowns during his reign.

The New Augustus

Ten years into his reign, Hadrian made it clear that he saw himself as a reincarnation of Augustus.1 Like the first emperor, he sought to consolidate power, reform the military, and strengthen Rome’s borders. But Hadrian’s Augustus-complex wasn’t just about ruling; it was about leaving a mark. He adorned cities with new temples, revived classical Greek culture, and made it known that he saw himself as a ruler not just of Rome but of civilization itself. I think that Hadrian’s most noteworthy building project was the revival of the Pantheon in Rome. He also had a pretty sweet (and massive) villa outside of Rome.

The Emperor of the People

Despite his immense power, Hadrian had an informal and approachable style. He could converse with soldiers, senators, and commoners alike, and he relished the company of intellectuals and artists. This won him a reputation as an ostentatious lover of the common people, a rare trait among emperors who often preferred distance and grandeur. I like this trait a lot. In modern times, we have so many examples of “leaders” who surround themselves with sycophants, hearing what they want to hear and creating division.

A Life of Wandering, A Legacy of Stability

Hadrian’s relentless travels were more than just an emperor’s whim—they were a statement of how he viewed leadership. To rule Rome, one had to understand Rome. From the windswept frontiers of Britain to the opulent temples of Athens, Hadrian left his mark on history not just as a ruler but as a traveler, a builder, and a man who believed that an empire was only as strong as the connection between its leader and its people. Adding my two Hadrian coins to my collection has allowed me to really focus on the research behind this impressive leader. While Marcus Aurelius may get a ton of credit (and deservingly so,) let’s not overlook the amazing triumph’s of Ancient Rome’s traveling Emperor.

Citation1: Everitt, A. (2009). Hadrian and the triumph of Rome. Random House Trade Paperbacks.

Disclaimer: As I journey further into the world of Ancient Rome, I have already begun to understand each ruler’s lasting impacts- good or bad- and the legacy they left us with. History is a hobby for me, and I do my best to remain accurate and based on sources. Please leave a comment on the suggested edits and changes. Again, this is a past time of mine and I make no claims to be a historian 🙂

Leave a Reply