Welcome to another post! I think my history buff readers will appreciate this one, and perhaps my political science fans will as well. We begin our journey by rewinding to the First-Century BCE, when Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 BCE. Now, dear Reader, I am not going to make this post an ultra-history lesson. We can save that for much, much better sources (and I make no claims to be a historian; rather a seeker out of every kind of curiosity.) With these caveats in mind, let’s cross our own Rubicon!

Ancient Rome had a very strict rule insofar as legions were not allowed to cross the boundaries of the City of Rome. Rome was limited mostly to the Praetorian Guard whose sole job was to protect the Emperor and keep the peace in the city. One thing to keep in mind is that Ancient Roman armies were much different than what we would consider an entity like the US Army to be. The commanders of each legion “owned” the army; that is, the soldiers were loyal to that general before they were loyal to the people and body of Rome. This is why paying and providing for your army was so critical. It was easy back then. Are your legions bored? Go sack and plunder a Gaulic town!

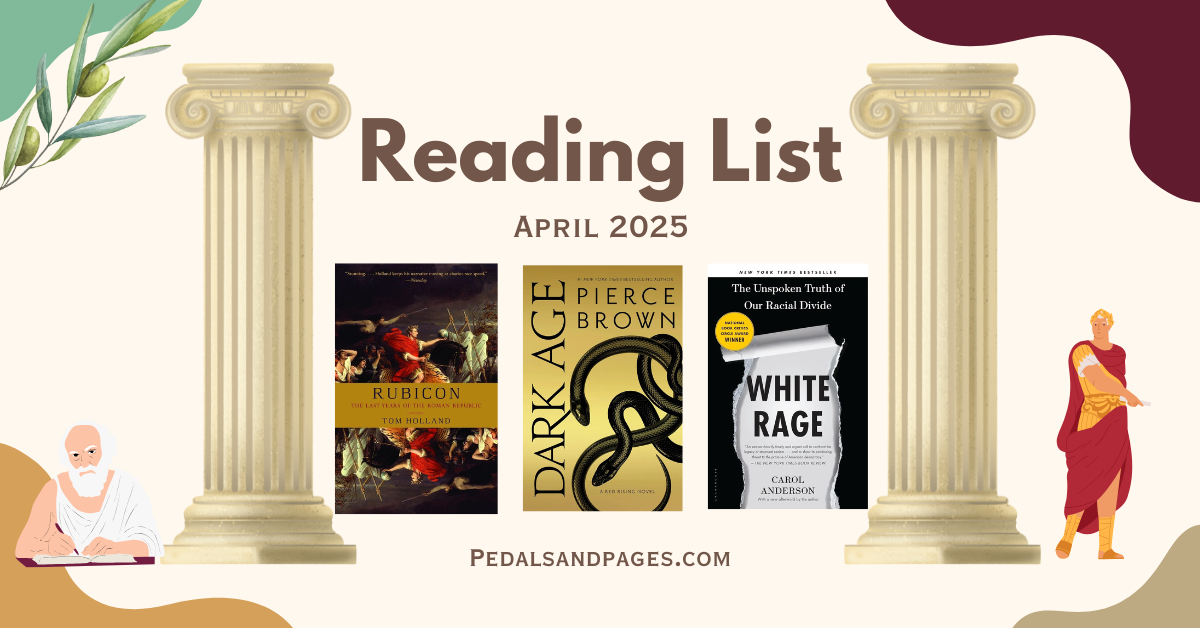

I am going to skip a lot of detail, and I recommend that you look into sources, such as Tom Holland’s Rubicon book!

Crossing the Rubicon

Caesar begins his autocracy by crossing the Rubicon in 49 BCE. This is a direct threat to the Republic and is not taken lightly. We use the term “Crossing the Rubicon” to this day to signify events around the world that have no point of return (think of the September 11th attacks.)

After seizing power, Julius Caesar implemented sweeping reforms, including creating the Julian calendar, reducing debt, expanding the Senate, and granting citizenship to people in various territories, while also solidifying his power and ruling as dictator. Again, I am just brushing the surface here but the important takeaway is that Caesar disrupted the order of things. Keep in mind that Ancient Rome was shrouded in civil wars and internal struggles—we even refer to Caesar’s rise to dictatorship as the Caesar Civil War.

Death Begets Death Begets Death

On March 15, 44 BCE, Gaius Julius Caesar was stabbed to death by a group of senators during a Senate session at the Curia of Pompey, within Rome’s Theatre of Pompey. Led by 60-70 senators (we will never know the true number,) Caesar was stabbed ~23 times. To me, the Ides of March crossed its own Rubicon insofar as the assassination of Caesar triggered an unstoppable chain reaction that would change Ancient Rome, and the world, forever.

The Downfall of the Roman Republic

So the Romans killed a dictator, big deal. It happens all the time and it will continue to happen in the modern world. Humans have this vanity of sorts in which autocratic rule never seems to last long (Adolf Hitler is a perfect example of this.) Indeed we could have quite the interlocutor about historical downfalls, but I want to shift focus back to Ancient Rome. And, yes, even Imperial Rome died (albeit much, much slower than some other autocratic bodies.)

Interestingly, the death of Caesar does not magically restore the Roman Republic. In fact, Rome will never go back to the old way. The die has been cast, and Rome will never be the same. As someone looking back with hindsight, the craziest aspect of this whole period is that Caesar’s heir actually assumes the role of Emperor. In 27 BCE, Octavian became emperor Augustus, and thus he finally terminated the Roman Republic. Yikes!

The Question

Dear Reader, I implore you to ponder on one simple question: was Ancient Rome better off as a republic or empire? What metric(s) are we using to determine what is “good” or “bad”? Are we basing this off of quality of life, or how many parcels of land conquests bring into the Empire, etc.

We will never arrive at a foregone conclusion. These artifices have been argued since the downfall of the Republic, and I don’t think that any one answer is correct. It’s what makes history such a fascinating topic to explore; we can ponder until we’re blue in the face.

Nothing Lasts Forever

Ancient Rome had its good, and bad, share of Emperors. From Hadrian to Nero, the mix was quite interesting. Indeed, most emperors died at the blades of conspirators, but there were some good ones sprinkled about (such as Marcus Aurelius.) Insofar as we are concerned, I believe that the theme I am going for here is that the world is in constant flux. I implore you, dear Reader, to get your bookkeeping in order; find what matters and begone with distractions and devices of man. Thus is the argument that autocrats sow the seeds of their own peril. The populous eventually rejects autocracy, like the senators of Ancient Rome. The bigger issue lies with the vacuum that is created after the autocrat is dead. How will history remember us in 20 years? 2000 years?

And at any rate we will all be gone soon enough!

Because, just as with the Ides of March, change can strike without warning—the die is cast, and history pivots onto an unforeseen trajectory.

Leave a Reply